PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

ERIC NEWMAN DISCOVERS AUDUBON'S FIRST ENGRAVED ILLUSTRATION

Eric Newman is a numismatic research machine, and his latest discovery is causing a sensation outside the numismatic world, as chronicled in articles this week in The Philadelphia Inquirer, the St. Louis Business Journal and elsewhere. I'm half his age and most days I couldn't find my own keister with both hands. But here's Eric at 99 making (yet another) important numismatic discovery. Way to go, Eric!

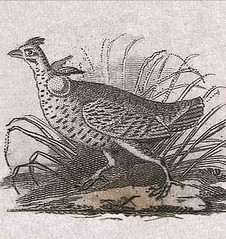

I've quoted extensively from the Inquirer article. The images are of Audubon himself, and Audubon's first engraved illustration, a grouse. -Editor For more than half a century, scholars and biographers of famed bird artist and ornithologist John James Audubon had been stumped.

It would have been a key moment - the first published illustration for the struggling artist, then 29 years old.

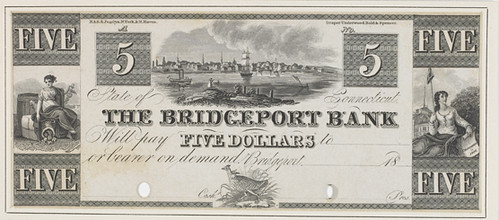

But Robert Peck, curator of art and artifacts at the Academy of Natural Sciences, decided to give it one last try. What he and Eric Newman, a numismatic historian from St. Louis, found has rocked the world of Audubon scholars, who are calling their discovery "a eureka moment." Their quest began about a decade ago, when Newman visited the academy as part of a tour of libraries and important collections. He and Peck met. They had lunch. A year later, Peck wrote to him. Had Newman ever seen a New Jersey banknote with a bird on it? Newman was an expert on the early paper currency of America and had written a definitive work on the subject. He didn't know of any, but he began looking. On a trip to Chicago, Peck checked another diary, and found an entry from 1826. Audubon was in England, where his landmark book, The Birds of America, with full-size printings of his bird watercolors, was eventually produced, beginning in 1827. He noted that he presented a friend "with a copy of Fairman's Engraving of [my] Bank Note Plate." But had the money ever been printed? Or was it a plate that never got used? Newman combed through every book written on New Jersey paper money. "That didn't help me at all," he said. Then he checked the 10,000 different banknotes issued in the United States for grouse pictures. "I couldn't find any." Finally, he reexamined his own collection of "sample sheets," printed with various images that bank presidents might want on their bills. Mostly, such sheets contain portraits of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, images of draped Lady Liberties, and, above all, eagles. But finally, on a sheet issued by Fairman's firm, likely in 1825 - there! on the lower right! - was a grouse. As was typical, the image wasn't signed. But while other wildlife artists of the day were producing static images, this had unmistakable Audubon touches - the unusual choice of species, the running posture that revealed a knowledge of the bird in the field, and hints of its grassy habitat. "All the circumstantial evidence lines up," Peck said. "He writes in diary twice he did this drawing for Fairman. And that it was of a grouse. And that it was for a New Jersey banknote. "And here, suddenly within months of Audubon saying he gave it to Fairman, the grouse appears on one of Fairman's sample sheets." More searches led to more tidbits. Eventually, Peck and Newman put together a likely scenario: Bills may have been printed for the New Jersey institution, the State Bank at Trenton, which employed Fairman's firm to design and print many of its bills. But the bank began to fail in July 1825, and its notes were worthless by 1826. The Camden bank eventually recalled its currency and burned it along with bills from the Trenton bank. "The failure and scandal . . . all that is documented as part of banking history," Peck said. Whether the burned notes actually contained Audubon's grouse is likely, given the timing, he said, but unproven. Peck and Newman also found later designs with Audubon's grouse - a $3 note for the Bank of Norwalk in Ohio and a $5 note for the Bridgeport Bank in Connecticut. But there's no evidence that either bank followed through and printed the bills. The academy announced Peck and Newman's findings Thursday. They're being published in the fall journal of the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic, based at the Library Company of Philadelphia. As word got out, scholars began calling with congratulations - and more tidbits. "It's been one of the holy grails for Audubon researchers, to find out if that exists," said Nancy Powell, curator of collections and exhibitions at Mill Grove. Now, "it lets us know a little more about him and his art and how he developed it." "It's the eureka moment where you find that missing piece of the puzzle," said Roberta Olson, curator of drawings at the New York Historical Society. The society has all 435 original watercolors for Audubon's Birds of America. One is of a similar grouse - the pinnated grouse - and the society dates it to 1824, the same year Audubon supposedly made the image for Fairman. Peck and Newman know they may never learn the whole story. So much is gone. But neither Peck nor Newman can resist the tantalizing possibility that banknotes with Audubon's grouse on them were printed and still exist . . . somewhere. Given the Trenton and Camden bank connections, they can't help but imagine some tucked away in a Philadelphia attic or stuffed into a Camden wall for insulation. "That is always possible," Newman said. "Always."

To read the complete article, see:

Eureka! Audubon's first engraved illustration discovered

(www.philly.com/inquirer/local/20100730_Eureka__

Here are some excerpts from the St. Louis Business Journal article.

-Editor

Retired St. Louis businessman and philanthropist Eric Newman has taken part in one of the greatest historical “finds” of late: John James Audubon's first published illustration of a bird. Robert Peck, curator of art at the Academy of Natural Sciences, told the Business Journal he met Newman 10 years ago when the St. Louisan was visiting Philadelphia museums. On learning of Newman's expertise, Peck enlisted him to join in the search for the early Audubon sketch. Newman suggested following the work of period engravers. As it turned out, Audubon had given his sketch of a heath hen, a now-extinct species of prairie chicken, to bank note engraver Gideon Fairman to try to sell his artwork.

The two researchers began looking at proof sheets Fairman had done for bank clients, and found the sketch on proof bank notes made for at least two independent banks in Connecticut and Ohio. The proofs were in Newman's own collection, Peck said.

Newman said several of the items are on display at the Newman Money Museum, housed in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis. Newman, now 99, retired about 1985 as secretary and general counsel of St. Louis-based shoe and apparel retailer Edison Bros. Stores Inc. He began researching and speaking on the history of money as a young teen, and “I've been writing on the history of American money for 80 years,” he told the Business Journal. “I have a lot of fun doing it.” In 1958, he founded the Eric P. Newman Numismatic Education Society. Newman has published more than 100 articles, monographs and books on the topic, he said. Newman said he doesn't charge for his research.

To read the complete article, see:

Numismatist Newman makes Audubon find

(www.bizjournals.com/stlouis/blog/2010/07/

There was also coverage in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, with a nice picture of Eric and his wife Evelyn.

-Editor

The discovery in and of itself is intriguing - but what makes it more so is Newman's age - he's 99.

Newman is a St. Louisan whose many publications include a book on Early American paper money that is considered the standard in the field. He also has one of the finest private collections of U.S., and Colonial American coins and paper money and his gift to Washington University established the Newman Money Museum. Newman and his wife, Evelyn Newman, 90, are at their summer home in Martha's Vineyard so their son Andy Newman, of St. Louis, answered a few questions on his father's behalf. "He's not doing anything to celebrate," Andy said. "Solving numismatic mysteries is my dad's passion. He tells me he has more in the pipeline." Andy said his father recently finished work on the fifth edition of his book about Early American paper money. While Andy was putting away some of the material he said his father stopped him and said, " 'Don't put that away. I'm working on the sixth edition.' "

To read the complete article, see:

Local numismatic scholar Eric Newman's discovery of an Audubon etching has set the scholarly world afire

(www.stltoday.com/news/local/columns/deb-peterson/article_0cf6c798-9c29-11df-9a25-0017a4a78c22.html)

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|