PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

SOME PANDEMIC HISTORYThese articles I came across this week are in the non-numismatic category, but should be of general interest in these times. First, here's an excerpt from a New York Times article on the birth of social distancing. -Editor The concept of social distancing is now intimately familiar to almost everyone. But as it first made its way through the federal bureaucracy in 2006 and 2007, it was viewed as impractical, unnecessary and politically infeasible. "There were two words between ‘shut' and ‘up'" initially, said Dr. Howard Markel, who directs the University of Michigan's Center for the History of Medicine and who played a role in shaping the policy as a member of the Pentagon research team. "It was really ugly." Dr. Mecher was there when Dr. Hatchett presented government public health experts the plan that the two of them and Dr. Lisa M. Koonin of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had reviewed over burgers and beer. "People could not believe that the strategy would be effective or even feasible," Dr. Mecher recalled. But within the Bush administration, they were encouraged to keep at it and follow the science. And ultimately, their arguments proved persuasive. Good ideas can start anywhere - even with 14-year-olds. -Editor

It was about that time that Dr. Mecher heard from Robert J. Glass, a senior scientist at Sandia in New Mexico who specialized in building advanced models to explain how complex systems work — and what can cause catastrophic failures. Dr. Glass's daughter Laura, then 14, had done a class project in which she built a model of social networks at her Albuquerque high school, and when Dr. Glass looked at it, he was intrigued. Students are so closely tied together — in social networks and on school buses and in classrooms — that they were a near-perfect vehicle for a contagious disease to spread. Dr. Glass piggybacked on his daughter's work to explore with her what effect breaking up these networks would have on knocking down the disease. The outcome of their research was startling. By closing the schools in a hypothetical town of 10,000 people, only 500 people got sick. If they remained open, half of the population would be infected. "My God, we could use the same results she has and work from there," Dr. Glass recalled thinking. He took their preliminary data and built on it by running it through the supercomputers at Sandia, more typically used to engineer nuclear weapons. (His daughter's project was entered in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in 2006.) Dr. Mecher received the results at his office in Washington and was amazed. If cities closed their public schools, the data suggested, the spread of a disease would be significantly slowed, making this move perhaps the most important of all of the social distancing options they were considering. To read the complete article, see:

Of course, social distancing itself isn't really new - just some of the science around it. Here's some historical background on the goal of "flattening the curve" from the University of Michigan. -Editor

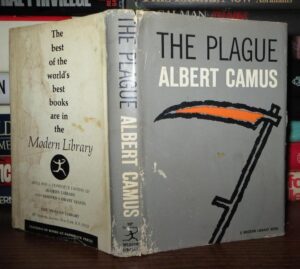

The historian was Howard Markel, director of U-M's Center for the History of Medicine. (He is both a pediatrician and the George E. Wantz Professor of the History of Medicine.) The administration asked the task force: What should we do if the avian flu — or any other viral epidemic — gets really, really bad? Markel, with colleagues from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, got to work. First, he recruited staff — a dozen or so researchers to gather every surviving scrap of information about the United States's response to the "Great Influenza" of 1918-19, at the tail end of World War I. They combed through every edition of the U.S. Census Bureau's Weekly Health Index for 1918-19; reports issued by city and state health departments; 86 newspapers; records of military encampments; and every published account of the pandemic they could find — more than 20,000 documents in all. They documented activities now familiar in 2020 — school closings; bans on concerts, movies, and sporting events; efforts to isolate the sick and quarantine those who'd had contact with the sick; business closures and staggered hours; restrictions on trains, buses and trolleys; and ordinances to require face masks. All 43 cities used non-pharmaceutical interventions. Some acted early, comprehensively, and for long periods. Other efforts were late, half-hearted, and brief. "They didn't cure the influenza," Markel said. "It was just about buying time." So the White House got the advice it had asked for: If a pandemic arose in the 21st century, every effort should be made to promote early, strong, and persistent non-pharmaceutical interventions in the lethal period before the production of a vaccine. Markel has been much in demand among journalists who want to know what he thinks will happen next. He is careful to say that historians are not in the business of predicting the future. But he points to the evidence of 1918-19 for guidance. "The key word about this coronavirus is ‘novel,'" Markel told the New Yorker recently. "We don't have any experience with COVID-19. We won't know it's over until long after it's over, so it's hard to know when to release the trigger. "This I know," he continues. "If we release these measures too early, we're going to be back in the same situation that we were in, in terms of cases and deaths, or perhaps worse, and we will have crippled the economy and caused all this social disruption for nothing." Markel teaches an undergraduate course on literature and medicine. Among the books he assigns is Albert Camus' The Plague, a novel set in French Algeria after World War II. In the city of Oran, rats infect humans with the bubonic plague. Officials downplay it, then dither. Panic and violence ensue, triggering martial law. When the pestilence finally subsides, the survivors are all too ready to forget their lethal folly. To read the complete article, see:

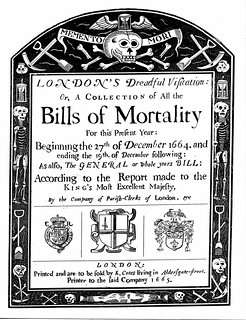

For additional timely reading, check out Daniel Defoe's 1772 A Journal of the Plague Year. -Editor The government acted swiftly. Invoking emergency measures passed in earlier times, the mayor issued a series of orders that aggressively changed life in the city. Public events and gatherings were banned, schools were closed and the city was divided into more readily policeable quarters. Infected individuals were locked in their houses with their families and were forbidden from leaving under the penalty of death. Upstanding citizens, deputized in various capacities as searchers, examiner, and watchmen, were — under the penalty of death — tasked with overseeing this quarantine. The city in question is not Wuhan or Milan or Manhattan. It is London and the year is 1665. Before the end of 1666, the Bubonic Plague will kill roughly one-quarter of the city's population. As devastating as this figure is, it could have been much worse. This is one of the key takeaways from Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year. Published in 1722, Defoe's text is technically a novel, but historians and epidemiologists have praised it as an accurate report of life in London during "the Great Plague." Defoe, who is most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe, did live in London in 1665, but he was only five years old. In A Journal, a middle-aged narrator renders a graphic and comprehensive look at life inside a city beset with a pandemic far more terrifying than the one we face today. To read the complete article, see:

And don't forget Samuel Pepys' first-hand accounts of life in London under the bubonic plague. -Editor

Pepys continued to live his life normally until the beginning of June, when, for the first time, he saw houses "shut up" – the term his contemporaries used for quarantine – with his own eyes, "marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord have mercy upon us' writ there." After this, Pepys became increasingly troubled by the outbreak. He soon observed corpses being taken to their burial in the streets, and a number of his acquaintances died, including his own physician. By mid-August, he had drawn up his will, writing, "that I shall be in much better state of soul, I hope, if it should please the Lord to call me away this sickly time." Later that month, he wrote of deserted streets; the pedestrians he encountered were "walking like people that had taken leave of the world." To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|