PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE HISTORY OF REDESIGNING AMERICA'S MONEYEllen Feingold is curator of the National Numismatic Collection at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Kellen Hoard passed along her February 15, 2021 Politico article about past and potential future changes to American currency. Thanks. Here's an excerpt - be sure to read the complete article online. -Editor Less than a week after taking office, the Biden administration announced it would restart Obama-era plans to redesign the $20 bill, replacing the portrait of President Andrew Jackson with that of abolitionist Harriet Tubman, after more than four years of uncertainty about the note's future. The decision has revived a fervent debate about who belongs on our currency, and whether the change is just another example of so-called cancel culture at its worst. It's not hard to understand why some Americans might see the redesign as a radical break from tradition. For the past century, U.S. banknotes have featured a static set of Founding Fathers and presidents, government buildings and national memorials. This 20th-century consistency created the illusion that significant design alterations would sever our currency's ties to its past. But this is a misperception. In the 1800s, currency redesigns were not at all uncommon. In fact, banknotes changed regularly, and featured a vibrant range of people, scenes and symbols. The United States did not have standardized designs depicting only a handful of political figures until the 1920s. What this history suggests is that we should not shy away from rethinking our currency today. Instead, the new $20 bill should be merely a starting point, encouraging us to think more expansively and creatively about the images that appear on our money—as we have in our past and as other nations do today. Money, after all, is a powerful means of communication. It is a missive we send around the world—an ambassador of sorts. It is also part of our national identity and can help to remind us of our common purpose. Our money should not only reflect our country's origins, but also who we have become over the past 250 years—as well as who we aspire to be.

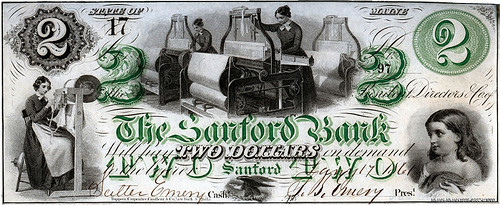

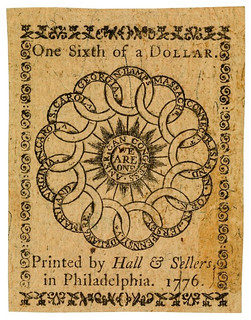

Historic figures began to appear on circulating banknotes in the early 1800s, but they were far from the standard or dominant imagery. Early American banknotes featured a dizzying array of allegorical and historic figures, scenes and messages. This remarkable diversity is a reflection of the wide range of institutions that issued currency. At the time, it was not the federal government that produced these bills, but more than 8,000 private banks and businesses, which had the freedom to determine what and whom to depict.

To read the complete article, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|