PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

ON THE FADING OF DIGITAL IMAGESPeter Huntoon submitted the following, which happened to land in our April Fool's issue. This was not a joke on his part. It is something we should get to the bottom of. There may be something occurring that all of us should be aware of. Your experiences, suggestions and comments will be most welcomed. -Editor

Fading of Digital Images

Peter Huntoon I have tens of thousands of moderate (300 dpi) to high-resolution (1600 dpi) digital images of U.S. currency, Bureau of Engraving and Printing certified proofs, scanned National Archives documents, scanned historic photos, even family photos, both black and white and color. The vast majority of these are saved as JPEG images but in other popular formats as well. They are stored on the hard drives of my high-end HP Envy laptops and towers, in Western Digital external mass storage devices, on removable disks, etc. Many of these images are embedded in PowerPoint presentations, in WORD documents, etc. It is irrefutable that all of these images are fading with time. If this problem is not specific to me, then the issue is absolutely huge. Digitization of archival material has become an institutional mainstay. The personnel at the Newman Portal recently reported that they have surpassed capturing 5 million images. At the rate my images are deteriorating, they will be useless within half a century. Most of my photo archive has been assembled since 1990 and my PowerPoint documents and WORD files since 2000. Fading is progressive and is very obvious within 10 years. When I need to use older scans, it is necessary to load the image into a photo processor and significantly kick up the contrast. This salvages much of the image but loss of resolution is inevitable and the subtle shades are lost. You only get to do this a couple of times before the scan is ruined. When I recycle a PowerPoint presentation that is a decade old, it is necessary to pull out every image to enhance it as best as possible and reload it. I have raised this topic with a few purveyors and users of this technology. Reactions are surprising. The knee jerk usually is vehement denial. Next comes tech-savvy rhetoric implying that this is impossible with digital storage, that I am somehow an incompetent consumer of this technology who doesn't know secret handshakes to prevent loss, or worse. Hmm, sounds like good ol' 2020s American political discourse! What I desire is a dispassionate discussion. Before leaping in, it would help greatly if you would look at your oldest digital images to see how they are faring. All of you who are into archival work already have been plagued by photographs, microfilm, sound recording, photocopies, etc., that have faded with time. Could it be that I am serving as the canary in the cage in this digital coal mine? This issue deserves serious dialogue by serious people. If real, it is big. When I pulled American Numismatic Association Curator Doug Mudd into the discussion, he replied seriously. -Editor

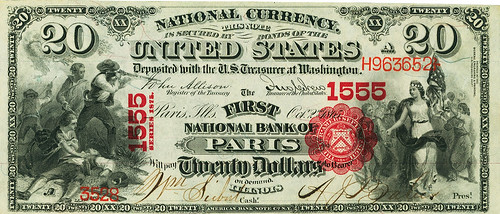

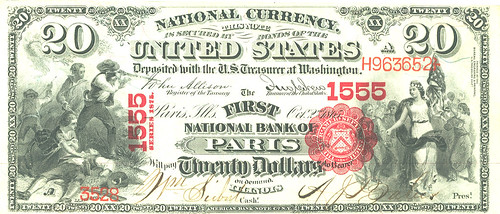

"Interesting... I have not experienced this except in cases where jpeg images have been repeatedly saved - so here are my thoughts on the origin of this problem. The jpeg image format is well known as a "lossy" format, i.e. each time you save a jpeg, it loses some of its information - this is because it was designed to be used on the web, where memory space was at a premium - so the jpeg format uses an algorithm to compress an image's information (to different levels as you can see when you save a jpeg in photoshop - you can chose the amount of compression, but even with the least compression, there is information loss). That is why tiff, psd, and more recently, raw image "non-lossy" formats are recommended for archival purposes - as I understand it (but I cannot guarantee this), there is no loss with these image formats. Unfortunately, these formats are unusable in most common applications, particularly for use on the web - and are much larger than their equivalent jpeg, gif and png format versions, which are the formats most used for online applications. I understand that the png format is recommended by archivists for web purposes as it is less lossy than jpeg. The size or resolution of the original image has nothing to do with the problem - it is all about the image format. "The one thing that I learned many years ago about digital image quality preservation, and have taught in my digital image classes ever since, is to ALWAYS save a master image - preferably in tiff or other stable format - though it works for jpeg as well. When you need the image, always use "save as" to create a new working image from the original (i.e. never "save" changes to the original master), which will prevent the loss of information from the original. I have not noticed fading from original images. "With that said, I will have to go back to some of my older powerpoints to check on if the images in them have faded (lost information) - but I believe that the only way that they can lose information is if the files they are saved in (word documents, powerpoint presentations, etc.) have been repeatedly saved, thus losing a bit of information from the embedded images each time. Anyway, I do not have a computer degree, but I have used photoshop and worked with digital images since 1993 or so." Note that Doug was talking about loss of resolution WHEN SAVING A FILE, not losses that occur in an otherwise unaltered file. And he's quite correct. These were the gag images and captions I added to the piece - they were not submitted by Peter. -Editor So can a digital file change over time? The knee-jerk reaction of myself and others is "No, of course not." But why do we believe that? For many it's a simple unquestioned assumption. For me it's my software engineering background and the work of pioneers such as Claude Shannon of Bell Laboratories, considered "the Father of Information Theory." Shannon was addressing data in transit, but the same principles apply to data at rest. One key element is the checksum, a number computed based on the digits within the message. The mathematics as proven by Shannon and others (and borne out by decades of subsequent research and experience), is that the probability of an incorrect checksum is infinitesimally small, and if the checksum matches then the data in the message was received correctly. So does this work for data at rest? Well, most commercial software relies on these checksums to validate files on input. The checksum is recomputed and compared against the checksum stored in the file, and if they don't match, the file is rejected as corrupted. So is that foolproof? Well, a skilled hacker could theoretically insert changes to both the data and checksum so that future readers of the file would be none the wiser. That gets into the principles of non-repudiation, a gold standard for databases that ensures the integrity and origin of the data in such a way that it can be independently verified and validated. Now most of our storage systems do not have such high standards, but it is also unlikely that an evil hacker organization is stealing our cultural heritage bit-by-bit to render files unusable over decades without anyone noticing. So what is Peter noticing? There may well be something going on at the file level, but there are other links in the chain to consider. Things that can change over time include:

And those are just the computer hardware and software. What about the external factors?

No one's got a time machine we could take back and revisit the original experience. But experiments could be done, doing the best to mitigate the above factors. What changes occur with differing hardware or software? Is there one key culprit that makes images appear faded? Who else has some old image files? How were they created and viewed back then? How do you view them now? How do they look to you? How do they look to others? -Editor

To read the earlier E-Sylum articles, see:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|