PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

KUENKER: GAMING COUNTERS AND NUMISMATICSOn 5 July 2025, Künker will offer a complete set of trictrac pieces at its auction 425. The ensemble is of great cultural and historical value. This prompts us to ask why gaming counters are part of the numismatic field – and what insights they can offer into the numismatic business of the early modern period. -Garrett Do you know trictrac? No? Even though the board used for trictrac resembles the backgammon board, trictrac is not a precursor to this popular game. Trictrac was played according to different, and much more complicated rules. These rules are so complex that we will not go into them here. Unlike in today's backgammon, the aim was not to move pieces from one point to another. Instead, players could score points through various combinations of the position of their pieces. The first player to score 12 points was the winner. A Game for the Nobility In trictrac, success depended on a combination of luck and a clever strategy. A lack of luck could be offset by great skill; however, even the luckiest dice throws were useless to the unskilled player. In this way, trictrac – unlike the purely intellectual game of chess – reflected the real life of the aristocratic upper class: after all, a good leader was someone who made the best of the cards fate dealt them. So it is no surprise that politicians and generals prided themselves on being masters of trictrac. Our oldest evidence of this game dates from the beginning of the 16th century and describes how young Federico Gonzaga played trictrac with Pope Julius II. By the mid-16th century, trictrac had arrived in Germany, where it was enthusiastically played by the nobility. In 1634, Euverte Jollyvet wrote a treatise on the game, characterizing it as follows: "Nearly all other games are as common among pages, servants and footmen as they are among princes, lords and nobles. [...] But regarding the Great Trictrac, only people of honor play it, and only the brightest, most agile and alert minds can understand it." Anyone who wanted to be "in" with high society learned to play trictrac, even the middle classes. Mastering the game became a status symbol. And even if you were a poor player, it was considered fashionable to have an expensive trictrac set in your home for guests to see. Just as many chessboards with elaborately designed pieces are used more for decoration than regular play today, trictrac boards adorned the sophisticated households of the early modern era. This increased the demand for precious gaming boards and pieces as the game became more popular. And this demand was met primarily in the two southern German centers of craftsmanship: Augsburg and Nuremberg. From Hand-Carved Counters to Machine-Made Products

Hand-crafted gaming counters, ca. mid-16th century, from the imperial art chamber. KHM Vienna. Photo: KW. In the mid-16th century, the craftsmen in Augsburg and Nuremberg were delighted about the new product, as it had a wealthy customer base. The Reformation had caused many wood carvers to lose their traditional customers. Nobody commissioned them to create depictions of saints to be worshipped at home anymore. Initially, the demand for elaborately crafted gaming counters filled this gap. However, it soon became apparent that the number of buyers who could afford hand-made counters and were willing to purchase them was incredibly small. This is when machine-made counters came in. In Augsburg, molds were developed to press motifs onto game pieces. Leonhard Danner, a Nuremberg toolmaker and inventor, developed this further. He had worked extensively with screws and presses, improving the letterpress among other things. Similarly, he was the first to use a press to transfer motifs on wooden pieces using metal dies. The trick was to adjust the screw press so that the motifs were sharp and deep without breaking the wood. Thanks to Danner's invention, Augsburg and Nuremberg developed into centers of counter production, but this came to an end in the early 17th century. The economic decline associated with the consequences of the Little Ice Age and the Thirty Years' War caused demand for all luxury goods to plummet. Friedrich Kleinert, an Entrepreneur from Nuremberg

Gaming counter with the portrait of the Palatinate count and marshal Friedrich Hermann von Schomberg. From auction 425 (3-5 July 2025), from lot No. 2242.

Medal commemorating the death of the Palatinate count and marshal Friedrich Hermann von Schomberg, 1690. Rare. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From auction 426 (7-8 July 2025), No. 3014.

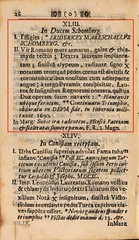

Excerpt from the catalog of available medals of the Nuremberg company: (left) Friedrich Kleinert of 1697 (center) Caspar Gottlieb Lauffer of 1709 (right) Caspar Gottlieb Lauffer of 1742 This brings us to Friedrich Kleinert, the Nuremberg entrepreneur who is responsible for the full set of trictrac pieces to be offered by Künker in auction 425 on 5 July 2025. If you cannot wait that long, there is a wide range of gaming counters available to choose from in eLive Auction 87. For eLive Auction 87 presents a special collection of board game pieces. But let us first turn to Friedrich Kleinert. Despite his importance to the German medal industry, we unfortunately know very little about this innovative entrepreneur. What we do know is that Friedrich Kleinert was born in Bartenstein, East Prussia, on 4 June 1633. After his father's death, Kleinert's mother remarried the wood turner Heinrich Machsen, and young Friedrich learned artistic woodturning from him. Like many other craftsmen, he embarked on a journey after completing his apprenticeship. In 1664, his path led him to Nuremberg. Initially, Kleinert worked in his craft there. It is said that he produced artificial dolls and similar items as a woodturner. Perhaps he also created simple game pieces. After all, the production of wooden blanks was the task of an artistic woodturner. In any case, Kleinert received a master craftsman's certificate and Nuremberg citizenship in 1668. However, it was not until he purchased a screw press in 1680 that Kleinert became a renowned medal producer. Innovative Technology: The Screw Press Screw presses were a new development in Germany at the time. In his catalog of available medals of 1742, Caspar Gottlieb Lauffer, a descendant of one of Kleinert's competitors, claims that his father was the first German to use a screw press. However, we have reason to doubt Lauffer's claim. After all, his next statement can easily by refuted: Lazarus Gottlieb Lauffer was certainly not the only private mint master to receive the imperial privilege to mint medals. On the contrary, in Nuremberg in the 1680s, four independent entrepreneurs, including Friedrich Kleinert, were minting medals with a screw press. We know this because, as early as on 8 November 1686, the Nuremberg Council discussed the new technology. The city fathers must have feared that the new machine could fall into the hands of immoral contemporaries. After all, excellent forgeries could easily be produced with a screw press. It was therefore decided that no private individual was permitted to use a screw press to produce circulation coins. It was only allowed to produce representative pfennigs, i.e., medals. Only four Nuremberg entrepreneurs were permitted by decree to own a screw press: Lazarus Gottlieb Lauffer, his brother Cornelius Lauffer, Johann Jakob Wolrab and Friedrich Kleinert. If any of them intended to sell a screw press or minting tools, they had to obtain the approval of the relevant official. The silver required for medal production was also subject to strict controls. It had to be obtained exclusively from the Nuremberg mint, and had to be alloyed with at least 15 lot and 2 quents of pure silver per mark. Last but not least, the Nuremberg Council tried to grant a monopoly to its engravers, as Nuremberg medal producers were only allowed to hire Nuremberg engravers. But this decision was revoked only a few days later: on 26 November 1686, Friedrich Kleinert brought about a new resolution which allowed him to "have his dies made in Augsburg so that the our metal engravers, who are surpassed by those in Augsburg, might be encouraged to be more diligent as a result". These two resolutions demonstrate the central role that Nuremberg played in the distribution of private medals. But how did collectors find out about Nuremberg medals? After all, an entrepreneur needed customers all over Europe if he wanted to operate profitably. Agents, played a central role in this. They worked for a prince and told them about all the offers that might be of interest to him. Those agents were called factors or court factors and procured works of arts for art chambers, as well as precious fabrics, weapons and furniture, books for libraries, and ancient as well as contemporary coins for coin collections. Great princes had agents in all important trading cities. Aristocrats of a lower rank and citizens, of course, did not. New Distribution Channels In 1697, Friedrich Kleinert followed in the footsteps of his colleagues in the book trade and did what they had been doing for decades: he compiled a catalog of all the medals available from his workshop. This catalog could then be sent to collectors. Needless to say, not every collector received an individual copy – book printing was extremely expensive back then! The catalogs were passed on among collectors and were repeatedly used to place orders with a local dealer who maintained a connection with Nuremberg. The fact that Kleinert wrote his catalog in Latin shows that he had customers all over Europe. Choosing Latin as the language of his catalog enabled him to ensure that all educated collectors understood his offer. What probably fascinates us most about this catalog is the fact that Kleinert rather casually included medals relating to events that had taken place long before the catalog was printed. Given how long such catalogs remained relevant, some events must have occurred several decades before a customer ordered the corresponding medal. Caspar Gottlieb Lauffer, who took over his stock of dies after Kleinert's death, published a new edition of this first catalog in 1709. In his much more comprehensive catalog of 1742, Lauffer switched to the German language. Kleinert's medal dies were still mentioned in this catalog. This means that collectors could still buy a medal commemorating Marshal von Schomberg even more than half a century after his death! A Lucrative Sideline

Gaming counters with allegorical topics. The translation of the legend on the first counters reads: It often squanders your gold. The legend of the second piece could be translated as: It's enough for the chest, but not enough for the eye. From auction 425 (3-5 July 2025), from lot No. 2242. All the producers of Nuremberg medals were thus private entrepreneurs who had to ensure that they produced goods that were easily marketable with minimal effort. In this context, counters for the fashionable trictrac game were a financially interesting addition to their business model that enabled them to re-use many of their dies. After all, very few dies were exclusively created to produce gaming counters. The series of the counters shown as figures 10 and 11 is an exception. The allegorical depictions were created and perhaps even conceived by the Augsburg engraver Jakob Leherr. Born in 1656, the goldsmith and engraver had held the title of master since 1685. And his designs are truly masterful. The little cupid looking into an overflowing chest is particularly impressive: It's enough for the chest, but not enough for the eye. Or, differently put, there is never enough for someone greedy. The same could be said of the creator of this game piece, Christoph Jakob Leherr. Alter all, by the time he produced these wonderful dies, he was already a prolific coin counterfeiter. The Nuremberg Council had been right to fear that the screw press would make counterfeiting easier! While Leherr produced coins, hie accomplice, the Augsburg merchant Emanuel Eggelhof, put them into circulation. Their activities went unnoticed for almost three decades. They were then exposed and the two were put to the sword in Augsburg on 10 April 1707. Therefore, it may seem almost ironic that Leherr also created these allegorical dies: the example with the head of Janus bears the inscription "cautious and prudent"; the fallen stilt walker illustrates the modern proverb "pride comes before a fall" or rather – as the Latin inscription says – "he is lifted up until he falls". Historical Gaming Counters

Game pieces commemorating the triple victory over the Turks and their allies at Peterwardein, Huy and on the Rhine border of 1694. From auction 425 (3-5 July 2025), from lot No. 2242. While most of the light-colored counters depict allegorical topics, the dark pieces were made with dies that Philipp Heinrich Müller had actually created for medal production. They deal with the politics of the time, although the events were probably long over by the time the game was made. This die, for example, commemorates the Habsburgs' victories over their enemies in 1694: at Peterwardein against the Turks; at Huy and on the Rhine border against the French.

Gaming counters commemorating the congress at The Hague of 1691. From auction 425 (3-5 July 2025), from lot No. 2242. Anyone looking for a deeper connection between the historical scenes depicted on the dark counters will search in vain. Logic was not required; only an impressive appearance. This board piece, for example, depicts the union of three virtues: strength, prudence and harmony. They join hands above an altar dedicated to the common good. The die was also created by Philipp Heinrich Müller and belongs to a medal issued for the congress of The Hague in 1691. A Completely Underestimated Field Let us get back to answering the question we posed at the beginning: gaming counters are a completely underestimated marginal field of numismatics that is closely related to medals in terms of production methods. After all, gaming counters were produced by the same workshops that created medals – even using the same dies and the same presses. Actually, board game pieces are medals made of wood. Anyone interested in this topic will be pleased to learn that, although they are much rarer than silver and bronze medals, these wooden medals are (still) considerably cheaper. This may be because the activities of the Nuremberg medal industry and its significance for European collecting have not (yet) been adequately researched. Unfortunately, most monographs on the topic of medals focus on the events they depict, on the nationality of the people depicted on them, or on the artists who created the dies. This loses sight of the fact that medals were goods whose appearance depended on the needs and the expectations of customers. But this could change soon. A new German work by Hermann Maué with the working title "Friedrich Kleinert and Philipp Heinrich Müller" is expected to be published in 2025. Hopefully, this book will acknowledge the importance of the numismatic entrepreneur Kleinert in full, without neglecting gaming counters.

Bibliography:

Wayne Homren, Editor The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: Subscribe All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|