PREV ARTICLE

NEXT ARTICLE

FULL ISSUE

PREV FULL ISSUE

THE MAN WHO INVENTED BOOKSELLING 1794 Halfpenny Token of J. Lackington Booksellers Has anybody mentioned this overlap of our interests - books AND coins - in a token issued by a London bookseller?

I don't believe we have. Ron sent a link to an eBay lot. Thanks. Here's the token.

-Editor

To read the eBay lot description, see:

It turns out that the bookstore was quite a famous one. Here's an excerpt from a 2016 article about it and it's popular owner.

-Editor

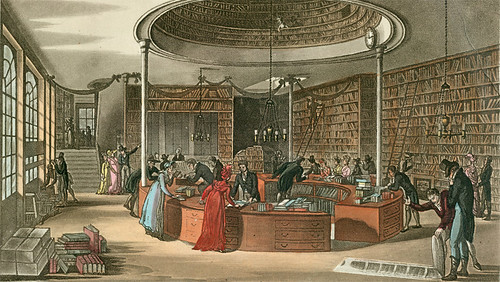

Today, few people are likely to remember James Lackington (1746-1815) and his once-famous London bookshop, The Temple of the Muses, but if, as a customer, you’ve ever bought a remaindered book at deep discount, or wandered thoughtfully through the over-stocked shelves of a cavernous bookstore, or spent an afternoon lounging in the reading area of a bookshop (without buying anything!) then you’ve already experienced some of the ways that Lackington revolutionized bookselling in the late 18th century. The Temple of the Muses, which was one of the first modern bookstores, was a mammoth enterprise, by far the largest bookstore in England, boasting an inventory of over 500,000 volumes, annual sales of 100,000 books, and yearly revenues of £5,000 (roughly $700,000 today). All of this made Lackington a very wealthy man—admired by some and despised by others—but London’s greatest bookseller began his career inauspiciously as an illiterate shoemaker. One of 11 children, Lackington was apprenticed to a cobbler as a boy. He had no formal education, but at an early age he recognized the value of books, and he and his friends scoured the markets for cheap editions of poetry, plays, and classical literature in translation in order to teach themselves to read and expand their understanding of the world. Later, as a shoemaker, he moved to London with his wife, Nancy, and years later in his memoirs he describes how, upon arriving in the city, he spent their last half-crown on a book of poems, Edward Young’s Night Thoughts: “For had I bought a dinner, we should have eaten it tomorrow, and the pleasure would have been soon over, but should we live fifty years longer, we shall have the Night Thoughts to feast upon.” Shortly thereafter, in 1774, Lackington was able to rent his own shop, and he began selling both shoes and books together. Late 18th-century London was a time of great social change. More people were learning to read, and the increase in leisure time among the working and middle classes meant an increased demand for books. But books were still an expensive luxury, and bookstores could be intimidating places. At the time, the typical bookstore did not encourage idle browsing or lounging. Lackington wanted to find a way to make books more affordable and accessible while still turning a profit, and with this in mind, he set about revolutionizing the book trade in at least four ways. His first innovation was to eliminate a staple of 18th-century commercial life: credit. He ran a cash-only business, which initially shocked his competitors and insulted some of his customers, but he reasoned that if he sold for cash, he could buy for cash instead of taking out costly loans; in this way he avoided interest charges as well as the losses incurred by customers unable to pay their debts. His second innovation had to do with his handling of remainder sales. The standard practice was for booksellers to buy large quantities of remaindered titles and then destroy as many as three-quarters of the books in order to drive up prices. But Lackington bought huge lots—sometimes entire libraries—and then drastically reduced the prices of all the books in order to sell them at high volume. In this way he kept books in circulation, made them affordable to a wider range of buyers, and turned a substantial profit all at the same time. Lackington’s third innovation will be familiar to anyone today who loves a bargain: he convinced his customers that they were getting a deal by refusing to haggle over prices. He posted this sign in his shop: The lowest price is marked on every book, and no abatement made on any article. By 1794, he had amassed a large enough inventory to move into a massive shop on Finsbury Square with his partner Robert Allen. He named the shop The Temple of the Muses, and above the entrance a plaque boldly announced: Cheapest Bookstore in the World. The Temple of the Muses became a tourist attraction, and this was Lackington’s fourth innovation: the sheer size of his bookstore—a spectacle that dwarfed all other bookshops of the time—made it a destination in itself. With a shop front 140 feet long, the cavernous lobby featured a circular counter with space for a mail coach and six horses to pass through. Above this counter, a staircase led up to “lounging rooms” where patrons could read beneath galleries lined with book-filled shelves, four floors in all. The higher patrons climbed, the cheaper and more tattered the books became. The poet John Keats spent many hours reading for free in the lounging rooms, and it was here that he met his first publishers, Taylor and Hessy, who worked in the shop. And like Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Lackington himself became something of a celebrity. A flag flew above The Temple of the Muses to let customers know when he was present in the shop, and he rode through the streets of London in a carriage inscribed with his motto: “Small profits do great things.” He even minted tokens bearing his image, which could be redeemed in the shop. A catalogue of his available stock was printed on a regular basis, and orders were filled for customers as far away as America.

To read the complete article, see:

The Numismatic Bibliomania Society is a non-profit organization promoting numismatic literature. See our web site at coinbooks.org. To submit items for publication in The E-Sylum, write to the Editor at this address: whomren@gmail.com To subscribe go to: https://my.binhost.com/lists/listinfo/esylum All Rights Reserved. NBS Home Page Contact the NBS webmaster

|